In September it was revealed that Facebook’s math just didn’t add up. At issue was how FB was describing its potential reach for advertisers.

“According to a recently published report, Facebook says they reach 1.5 million Swedes between the ages of 15 and 24,” noted this post in the Ad Contrarian. “The problem here is that Sweden only has 1.2 million of ’em. If Facebook reached 100% of them, they’d still be 300,000 short.”

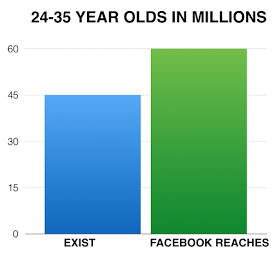

Missing Swedes weren’t the only issue; FB’s estimates the number of Americans between 24-35 it could reach was about 15 million more than physically possible:

Image source: The Ad Contrarian

Now, new reports are finding even more evidence of this kind of inflated reach estimates, explains Rick Edmonds in Poynter.org.

“Now the Video Advertising Bureau, a trade group for cable and broadcast networks and their sites, has a follow-up study saying that the internet giant is over-counting non-existent 18- to 24-year-olds in all 50 states,” Edmonds explains.

“Collectively, Wieiser and the VAB say, the company’s claimed reach exceeds census estimates by a third in the 18-24 demographic and 80 percent among 25-to-34-year-olds,” he continues.

This latest report joins a growing list of metric over-reaches for the social giant, including the video metrics problems that came to light last fall.

How can FB explain these issues? According to Edmonds, who spoke to a Facebook spokesperson, the numbers are “based on a number of factors,” and not necessarily census data.

To be clear, Facebook is not being accused of over-charging. “Its ads are generally placed by electronic auction, and the price is based on the numbers (views and a watch-to-completion factor) for a given ad,” Edmonds notes.

Rather, it’s using inflated claims for specific demographic potential reach, which may be swaying advertisers to choose Facebook over other potential advertising options, as they search for the digital ad unicorn we were all promised.

Sean Cunningham, President and CEO of the Video Advertising Bureau, thinks it’s time for Facebook to get in line with industry standards.

“Data innovation is a big part of what’s going to be good about the future of advertising,” Cunningham says, “but we need an equal view where everyone is looking at the same set of data.”

For Edmonds, the reach over-reach is part of a larger problem with the digital ad landscape in general.

“Just last week, the Financial Times said an internal study had found bogus listings for ft.com ads on a number of ad exchanges. It urged clients to step up verification to ensure against fraudulent placements.

“At the very least,” he continues, “as in the news domain, Facebook’s growing pains in advertising, both metrics and placements next to inappropriate content, are surfacing at a brisk rate and require regular remedial action.”

Will all of this impact their massive ad revenue growth, as advertisers realize the disconnect here? It’s hard to say. Clearly, as credibility remains at the forefront of consumer opinion, it’s well past time for the digital ad industry to grow up.