Jean Twenge is not a nostalgist, stuck in a hopeless longing for the good old days. She’s a professor of psychology at San Diego State University who has been researching generational differences for more than 25 years.

Jean Twenge is not a nostalgist, stuck in a hopeless longing for the good old days. She’s a professor of psychology at San Diego State University who has been researching generational differences for more than 25 years.

What she’s learning about the post-Millennial generation – those born between 1995 and 2012 – is deeply disturbing.

“Typically, the characteristics that come to define a generation appear gradually, and along a continuum,” Wenge writes in The Atlantic. “Beliefs and behaviors that were already rising simply continue to do so. Millennials, for instance, are a highly individualistic generation, but individualism had been increasing since the Baby Boomers turned on, tuned in, and dropped out. I had grown accustomed to line graphs of trends that looked like modest hills and valleys.”

Then she began studying the iGen generation, as she’s termed it.

“Around 2012, I noticed abrupt shifts in teen behaviors and emotional states. The gentle slopes of the line graphs became steep mountains and sheer cliffs, and many of the distinctive characteristics of the Millennial generation began to disappear. In all my analyses of generational data—some reaching back to the 1930s—I had never seen anything like it.”

What happened, she wondered, in 2012 to cause this kind of societal disruption? According to Wenge, that was the year that smartphone ownership in America passed 50%.

Since then, there have been significant drops in what, until now, has been typical teenage activity:

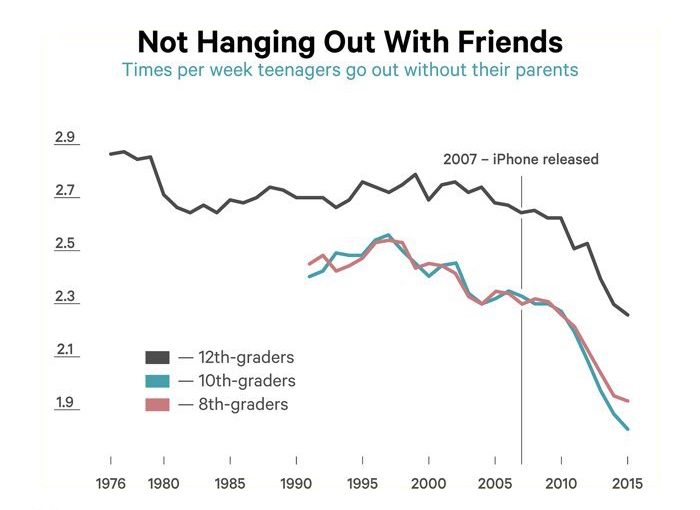

- They aren’t hanging out as much with friends;

Image source: The Atlantic

- They’re not in any big hurry to learn to drive;

- They date less;

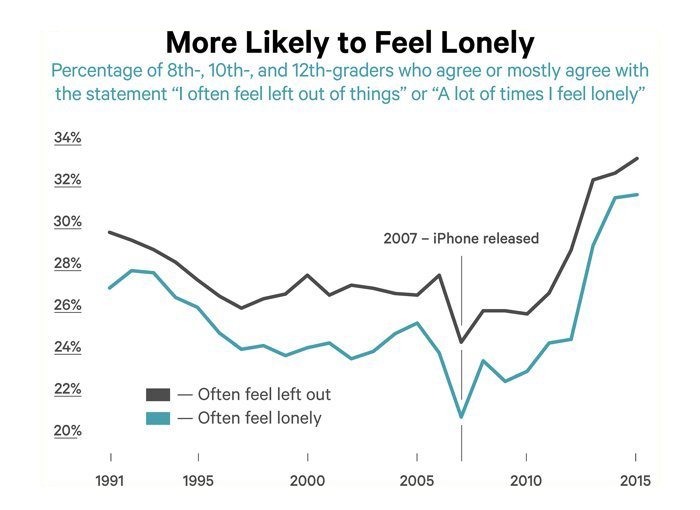

- They are significantly more likely to feel lonely;

Image source: The Atlantic

- And they are less likely to get enough sleep.

The above statistics (just a sampling from the original article) are from Monitoring the Future survey, funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and designed to be nationally representative. The survey has asked 12th-graders more than 1,000 questions every year since 1975 and queried eighth- and 10th-graders since 1991.

Wenge believes this is all linked to the amount of time these kids are spending on their phones. And it’s having a serious impact on their mental health.

“Teens who spend more time than average on screen activities are more likely to be unhappy, and those who spend more time than average on nonscreen activities are more likely to be happy,” she explains.

And Twenge is clear on this point — there is not a single exception to this rule. “All screen activities are linked to less happiness, and all nonscreen activities are linked to more happiness.”

“Those who spend an above-average amount of time with their friends in person are 20 percent less likely to say they’re unhappy than those who hang out for a below-average amount of time,” she notes. “Teens who visit social-networking sites every day but see their friends in person less frequently are the most likely to agree with the statements ‘A lot of times I feel lonely,’ ‘I often feel left out of things,’ and ‘I often wish I had more good friends.’ Teens’ feelings of loneliness spiked in 2013 and have remained high since.”

There’s also a significant feeling of being “left out,” when social media makes it so easy to see when you haven’t been invited to the party. Feelings of being ostracized and bullied online are taking an increasing toll; tragic media reports tell us how dangerous this can be.

Wenge believes we are facing a true mental health crisis with these kids. “Rates of teen depression and suicide have skyrocketed since 2011. It’s not an exaggeration to describe iGen as being on the brink of the worst mental-health crisis in decades. Much of this deterioration can be traced to their phones.”

The article does a fantastic job of diving deeply into the phenomenon and highlighting some key problems – the isolation, lack of sleep and the non-communicative lifestyle that all exacerbate the feelings of loneliness and unhappiness.

So what do we do? Wenge is clear; limit the screen time, and keep kids busy in healthy activities like working, sports, club activities that foster face-to-face interaction.

She knows it’s not realistic to eliminate the smartphone in our kids’ lives, but putting some limits on it – like anything else in life – is important. Especially at night, she notes.

“Electronic devices and social media seem to have an especially strong ability to disrupt sleep. Teens who read books and magazines more often than the average are actually slightly less likely to be sleep deprived—either reading lulls them to sleep, or they can put the book down at bedtime. Watching TV for several hours a day is only weakly linked to sleeping less. But the allure of the smartphone is often too much to resist.”

If you have teens in your life, it’s worth reading this and sharing. Then go talk to them, without phones, and see how they’re really doing. They might find some relief being forced to put that phone down for a while.