It’s all about the “thud.”

It’s all about the “thud.”

The physical experience of reading a book, according to Adam Sternbergh writing in LitHub in 2015, is what ultimately protects books from a digital demise.

“It’s different when you read a book. When you read a physical book, or you read an e-book, the physical experience of reading that book is different. It looks different. It feels different. It even smells different. Your memory of having read it will be different,” Sternbergh wrote.

When read on a screen, on the other hand, “all books … start to feel the same, as though dredged up from a vast grey ocean of pixels.

“Or you can read the exact same book—the same words, the same story, the same ideas, the same emotions—on paper, bound between covers, where you physically sense the heft of what you’ve read and of what you have yet to encounter,” he continues. “Where you can close the book with a satisfying thud when you are finished. Those are two very different experiences of the same book.”

Very different indeed, and that’s the reason why he believes the “future” of books has already come and gone.

Sternbergh cited e-book sales data from 2015 to back up his theory that e-readers, while they have their uses, won’t replace the printed book. More recent figures continue to support his idea.

Of course, science supports the benefits of reading in print, and consumer preference is strong. The tactile nature of print, far from being painted as nostalgic or romantic, is now supported by data that tells us what print lovers have always understood.

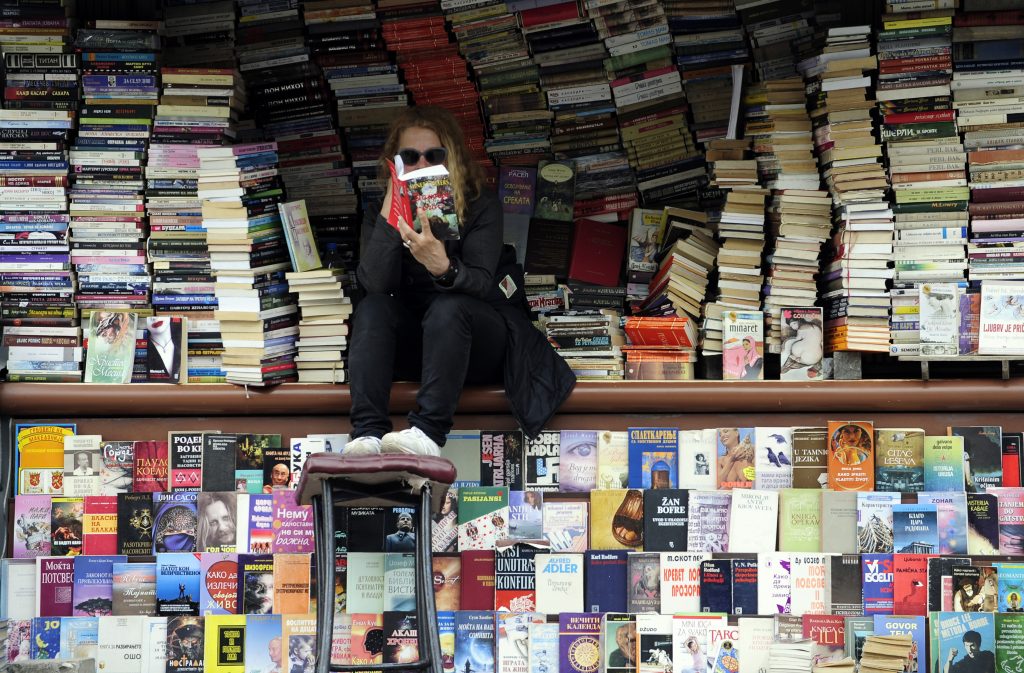

Part of the book reading experience is, of course, the bookstore itself, and this is another matter. Changing retail habits have certainly changed the way we discover and engage with books, and the bookstore is on the front line of this change.

Yet look at Cincinnati, where bookstore culture has achieved cult status. Clearly, book lovers abound, and the bookstore experience continues. Has it changed? Sure, as all cultural aspects do. Yet we agree with Sternbergh that it will not vanish.

“Again, I know I’m an outlier on this; not alone, exactly, but a member of a weirdo tribe. I’ve seen other people interact with books—crack them open, read them, chuck them without a thought—often enough to know that the true book fetishist is in the minority,” he explains. “But this recent good news about print books at least suggests my own experiences with books—real books—aren’t simply delusions. That the appeal of the physical book itself—its heft, its scent, the tactile quality of its cover, the give of the binding, the paperstock—is not a mirage that no one else can perceive. That maybe books have survived for 500 years for a reason, and maybe they’ll survive 500 more. That maybe books are different.”

Thud.